Major biological changes on the shoreline of Svalbard

Looking for animals in the seaweed in Kvalvågen, Svalbard

Top image: Eager researchers and students are looking for seaweed fleas (Gammarus setosus) – small shrimp-like animals – that live under rocks and in rock crevices on the shore. Here from Kvalvågen in Eastern Svalbard where no kelp can establish itself due to long-term ice cover and a lot of ice scrubbing. (Photo: Janne Søreide/UNIS).

Generally, people speak in negative terms when it comes to decreases in extent and thickness of the fjord ice in Svalbard. However, for the biodiversity and productivity at the shoreline, it can be very positive.

24 August 2021

Text: Janne E. Søreide, professor and Anna Vader, associate professor, UNIS; Malin Daase, researcher, UiT The Arctic University of Norway; and Josef Wiktor, senior researcher, Institute of Oceanology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Sopot.

More inflow of warm Atlantic water combined with milder winters has reduced the ice cover in the fjords on West Spitsbergen considerably. In the years 1973-2000, Svalbard was covered by 12,000 km2 of fjord ice, or more correctly land-fast ice, which is the term for sea ice frozen to land. In the period 2014-2019, the area was halved. If it gets only four degrees warmer in the winter, the land-fast ice will more or less disappear from Svalbard.

You will not find tall trees in Svalbard, but under water there are lush kelp forests! When the ice disappears, it allows seaweed and kelp to grow all the way to the surface, without the risk of being swept away by the ice. The absence of ice also provides more light into the water, which in turn allows the kelp forest to grow deeper.

Long series of measurements show that the distribution of kelp has increased fivefold along the west coast of Svalbard in the last 20 years. For fish and other animals that use the kelp forest as a grazing and growing area, this is very positive. Dense kelp forests that are several meters high is now found from the surface all the way down to a depth of 30 meters along the coast of western Spitsbergen. This is in stark contrast to the situation in the late 1990s. At that time, the shore along West Spitsbergen was more similar to the bare shore we currently have in the north-eastern parts of Svalbard, where the sea ice is still present for large parts of the year.

Seaweed and kelp monitoring

The big question is whether there will be a similar development in the north-eastern parts of Svalbard. To answer this, UNIS, in collaboration with other research institutions (see fact box), has started work on mapping the distribution of seaweed and kelp in Storfjorden and Hinlopenstretet.

These are areas that are demanding to get to. But with the help of a student cruise with the research boat Helmer Hanssen, the Coast Guard, and the small research boat Clione, as well as sending students on board Hurtigruten’s tourist boats, UNIS has in recent years still had access to the area. The researchers have collected data on the distribution of seaweed and kelp, as well as information about biodiversity and productivity of phytoplankton and zooplankton here.

This summer, four researchers and two students went with the Coast Guard’s KV Barentshav to Sørporten in Hinlopenstretet for the first time. Like most other boats, the KV Barentshavis not equipped with laboratories or winches and cranes for marine sampling. Still, with the help of a very helpful crew, two cabins furnished as laboratories (see photos), we collected many good scientific samples this year as well.

Using an underwater camera and acoustics, we saw that in Storfjorden and Hinlopenstretet we had to go down to a depth of 3 meters to find as dense kelp forest as in the western parts of Svalbard. On shallower water, there were only a few small kelp growths in rock crevices and under rocks, out of reach of the ice. It will be exciting to see the development ahead when the ice recedes further.

The small, important organisms

UNIS also monitors the species composition of phytoplankton and zooplankton using DNA tests. This is an important tool for monitoring the immigration of new species, both microscopic organisms and larger animals.

These small, very important organisms are also affected by the ice thickness and ice cover. Many benthic animals such as crabs and shellfish have larval stages that live freely in the water during their first year of life. Depending on the species, these larvae can drift with the ocean currents for several months before settling on the ocean floor again. We find mostly the same plankton species around the whole of Svalbard, but in different numbers. The most heat-loving species are most numerous along the west coast, while Arctic species dominate in the eastern and northern areas.

It was extra exciting this year when we found large deposits of small crustaceans in the water in Hinlopenstretet that usually live in the sea ice. We caught these with a small fine-mesh net that we trawled all the way to the surface (see picture). These crustaceans had probably lost their grip in the ice that melted quickly while we were there. These crustaceans have an annual cycle where they live on the ocean floor in shallow waters in the summer when the ice is gone, and then attach to the ice again when it freezes in the winter. Whether they can survive an entire winter or an entire year without sea ice is uncertain.

In the heavy drift ice in the Arctic Ocean, we find other species of crustaceans that can grow up to 6 cm long, and which are an important food source for fish and seals. In the Arctic Ocean, there are several thousand meters to the bottom, and it is likely that these crustaceans are dependent on the summer sea ice and will not survive in an ice-free Arctic. So, a warmer climate will result in many winners, but unfortunately also the loss of unique Arctic species.

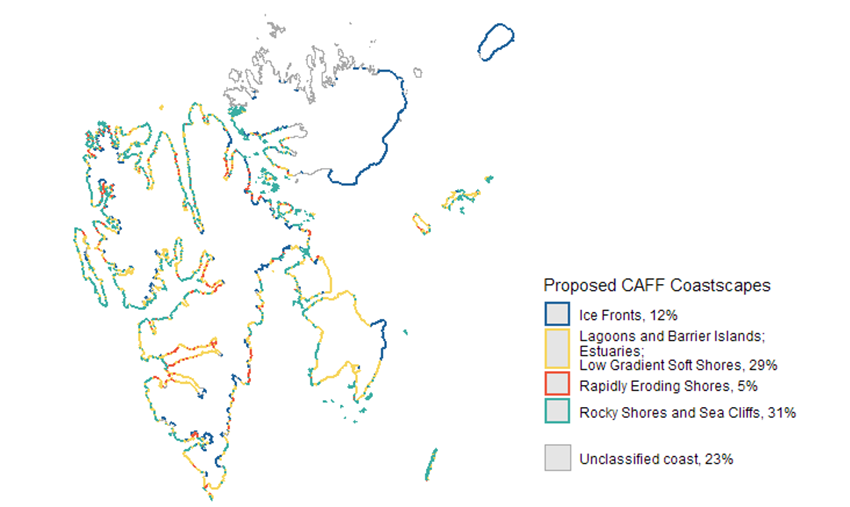

Interested in more information? Have a look at: Environmental status of Svalbard coastal waters: coastscapes and focal ecosystem components (SvalCoast) | Zenodo

Fact box:

The University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS), in collaboration with the Polish Academy of Sciences, the Norwegian Institute for Water Research and UiT The Arctic University of Norway, has for the past four years gone regularly to Eastern Svalbard to map the biological condition of coastal areas. This is part of a larger international project led by UNIS: ACCES (De-icing of the Arctic Coasts: Critical or new opportunities for marine biodiversity and Ecosystem Services?) The work will continue in a new large EU project: FACE-IT (The future of Arctic coastal ecosystems – Identifying transitions in fjord systems and adjacent coastal areas). In this EU project, UNIS and the Norwegian Polar Institute are important partners where the focus is on climate change in fjords on Svalbard and in Greenland.