Night at the Observatory

Photo: Maria Philippa Rossi/UNIS

Top image: The view from the roof of Kjell Henriksen Observatory is fabulous for northern lights-spotting, whilst keeping students safe from potential bears lurking around. Photo: Maria Philippa Rossi/UNIS

It sounds like a sequel to a sequel to a Hollywood-movie that was popular when today’s students were still in kinder. Nevertheless, for geophysics-students at UNIS, spending long nights at the Kjell Henriksen Observatory is a part of the game. And although polar bears might roam around outside, they are safe not to meet a T-Rex in the corridors.

24 February 2022

Text: Maria Philippa Rossi

We have barely left the minivan at the top of Gruve 7-mountain before the chatter is going like the students have known each other forever. Truth is, less than a month ago, the students were spread across five countries on two continents.

– Did you hear about SpaceX? one asks.

– So stupid, one of the facemask-balaclava-clad students answer.

– Costly mistake.

Someone did not do their homework, and that is unfortunate when your name is Elon Musk. Despite being good for some 239 billion USD, loosing 40 of 49 Starlink satellites in a geomagnetic storm is a blow.

Sophie Maguire explains.

– On February 3, Elon Musk and Space X launched 49 satellites, destined for the low Earth orbit, about 210 kilometres above Earth. Unfortunately, the satellites deployed on Thursday were hit by a geomagnetic storm on Friday. The geomagnetic storm increased the friction of the air by up to 50 per cent and caused the satellites to change their trajectory. Up to 40 of them never made it to the desired altitude and ended up back in the atmosphere, burning out.

– Costly mistake, she repeats and smiles. Not with malice, but with an inexhaustible fascination for space and what it contains. And how it is vastly unexplored, and how she wants to do something about it.

Night-time fieldwork

Inside the Kjell Henriksen Observatory, the “control room” is quickly filled with eager students in small groups in front of screens with cameras, graphs, dots, and lines. Their first task is to look at the real time solar wind data and calculate when it will hit the earth’s magnetic field, and – eventually – rain down in the atmosphere over us.

Sophie is accompanied by Chloe Lovatt, and they quickly locate the different numbers and dots.

– This is good. See here where it dropped? That means lots of northern lights – hopefully, she smiles.

– What is 1.5 million km/s divided by 393 km/s? Δt2 and Δ(t1+t2)?

The four groups end up with a 90-minute range for when the solar storms will hit us, and there is nothing to do but wait. And calibrate instruments.

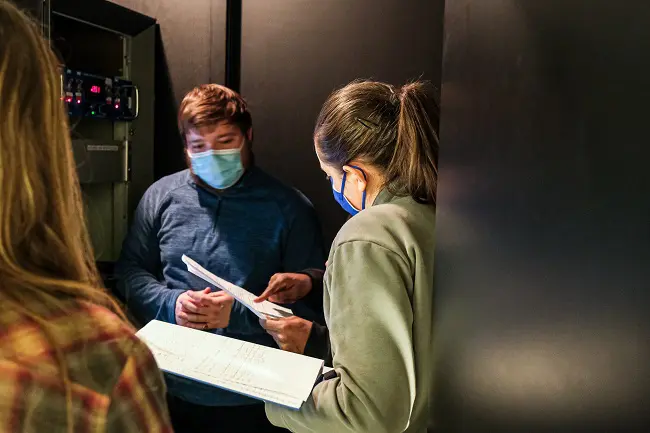

Post doc at UNIS, Katie Herlingshaw, brings three students into one of the instrument rooms. A four page long, quite detailed to-do-list aims to guide the students in calibrating the meridian scanning photometer, an instrument meant to measure the brightness of the different colours that make up the northern lights. A big warning sign outside the instrument room reminds us to turn off the high voltage power before entering.

– Did you remember, one of the students ask.

The other one goes to double check.

Look up! By all means, look up!

After the meridian scanning photometer is calibrated, we return to the control room where a new prediction has been calculated, now possibly keeping us at the Observatory all night…

Some students heat up their dinner, others have a cup of tea, and a small group is busy filling out the board with relevant solar wind data.

Suddenly there’s hustling and bustling and the students gather in the control room.

– Look! There are northern lights, there in the south!

Twelve people are quick to gather their warm clothes, cameras and tripods and climb up on the roof. The pro of having a roof, is that there is no need to bring a rifle.

And sure thing. Towards the south, a green scatter can be seen through the clouds. Cameras are clicking, ISOs peak, shutter speeds are played with.

– Stand still, someone yells, and the moment is perpetuated.

As the clock gets close to 1:30 AM everyone is happy, and we decide to call it a night. Red cheeks and smiling faces fill up the belt wagon as it rumbles down the mountain towards the parking.

Two students are quick to jump in the minivan front seat and connect their bluetooth for some sing-along on the ride home.

– It can be hard to go to straight to bed after a night at the KHO, Sophie explains.

– We have seen aurora, we have had good chats, we have learned lots of new things. The mind is spinning around, trying to encompass it all.

– Hey, who are up for pizza?