Robotic mapping of Svalbard’s marine forest

With the novel use of unmanned surface vehicles (USV), it has become safer and easier to collect data from glacier fronts. Master student Milan Beck is one of the first who utilised this sustainable way of monitoring the pristine and vulnerable Arctic nature for his thesis.

Milan Beck in Billefjorden. Photo: Børge Damsgård

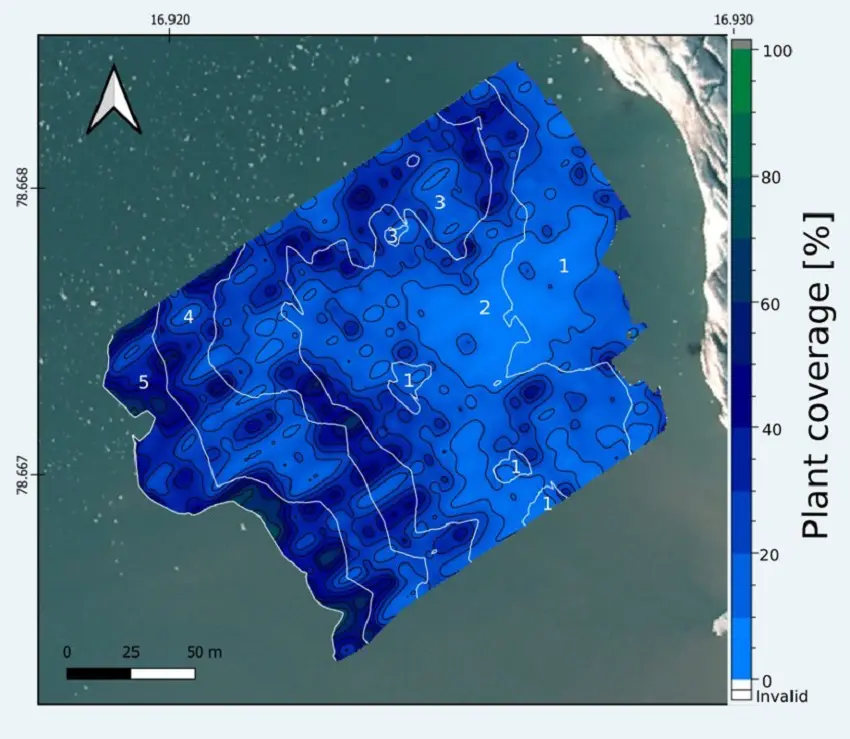

Beck’s thesis investigates macroalgae coverage around Billefjorden at different stations, presenting changing environmental conditions.

– We tried to link those genuine differences, I.e., in front of glaciers or river deltas to see if these differences can be explained by the environmental conditions.

– The USV is an exciting piece of technology that we tried out in the fjord, mapping the macroalgae efficiently, non-invasively and close to the shore, he says.

It is the first time an USV has been used in this configuration. Eccosounder has been tried previously, but the remotely controlled, easily deployable USV is a novel approach.

The biggest advantage with the USV is the possibility to reach very remote, and potentially dangerous habitats like glacier fronts where change is happening fast due to residing glaciers that causes huge discharge of fresh water. At the same time as the locations are important to study, these environments have been dangerous and difficult to reach. The USV has aided the process of collecting data.

– A lot of people are depending on the environment and the health of the environment. It is crucial to understand these processes, how they are modulated, and how it may change in the future, Beck says.

From the Mediterranean to Svalbard

Beck is originally from Berlin, Germany, and started his biology studies in Bremen, one of the major locations to study marine biology in Germany. For fieldwork he went to the Mediterranean, focusing on the microbiology aspect of the marine environment, mapping the novel microhabitat there, and implications for the changing environment, such as climate change.

– After that, I was on the lookout for an interesting topic for my master thesis. At a promotional day at my university, different institutions were presenting their projects. After Børge Damsgård’s talk, I was immediately interested.

Svalbard had always been a location where he wanted to go and study, so Beck contacted UNIS and ended up spending half a year in Svalbard in 2021.

Mapping marine forests

Børge Damsgård, professor in Marine biology and Beck’s supervisor, have spent many years in Svalbard. He says there are huge changes in the coastal zones. In the new EU project FACE-IT, UNIS is one of the partners that focus on coastal ecology, comparing such changes on the ecosystem biodiversity and biological functions in Svalbard’s fjords

– Most of the marine research is based on the use of bigger ships. But with bigger ships we must go further from land. The drivers of change, in light of climate change, should be understood close to land, not just out at sea.

After the spatial study, the scientists have seen signs of a changing environment, but hope that more funds and time are put into research on the topic. During the summer of 2022, a new PhD student will come to Svalbard and follow up the work at the same stations, to get a time series and see the development over time.

Damsgård explains that there are two approaches to the changes. One is to do long-time-series where you see changes. The challenge is that the time series do not necessarily dive deeply into the drivers, and the causes and biological mechanisms of these changes.

– We know it is a current climate change, but that is the broad picture. We need to dive deeper in the spatial changes. There are changes going on in the forest of the ocean. Most people do not see them. Most people do not see macroalgae, but there are big, big forests out there. It means a lot for the eco-system and for the environment. We have a forest, but it is underwater, Damsgård says.

Easier to standardise measurements

The glaciers studied in the project were terminating out in the sea just a couple of years ago and have now retreated onto land. The scientists have seen fast macro algae establishment in front of the glaciers.

– We are surprised about the magnitude of these ocean forests. They are much bigger than we first thought. But we have few studies to compare with, the closest comparison is from scientific diving, and individually quantifying how much macro algae there is along a diving line, Damsgård says and adds that the USV makes the data collection manageable.

The unmanned surface vehicle is really a small catamaran and is 1,5 x 1 metre. It is easy to transport on a boat and deploy whenever the researchers get in the field.

– That is the whole point, Beck adds.

– You can drive it autonomously on pre-drawn routes, which makes it very easy to standardise measurements at the different stations. You can make it drive the same transect lines. It can be equipped with a multitude of different sensors.

Custom built

Maritime Robotics, a technological company in Trondheim, Norway has built the USV. It is custom made and designed to meet UNIS’ needs.

– The USV is modular, and you can customise it depending on what instruments you need in the field. We have used a CTD-probe, measuring temperature and salinity and an echosounder to map the macroalgae. We have also attached a camera to get footage of the underwater community, overall, it is a very neat tool which makes fieldwork easier. It saves us a lot of time, which is crucial in the short Arctic summer season, Beck says.

Svalbard is a testing arena for emerging technology, and Damsgård says that the technology is continuously being developed.

– Previously, other universities have visited Svalbard, tested their equipment, and then left. This is the first time UNIS has invested in such USV technology and been in the forefront of the development.

During the sampling the researchers stayed safe, dry, and warm on bigger boats or in small field cabins. With a few clicks, they could instruct the USV to go exactly where they wanted and take the required measurements.

– It generates a lot of data that we can bring back and analyse. This would not have been possible to do with a regular boat. The last time a similar study was made in a glacial front, it was done with a helicopter flying in to take samples. That was clearly a quite difficult and horribly expensive way of data sampling, Damsgård concludes.